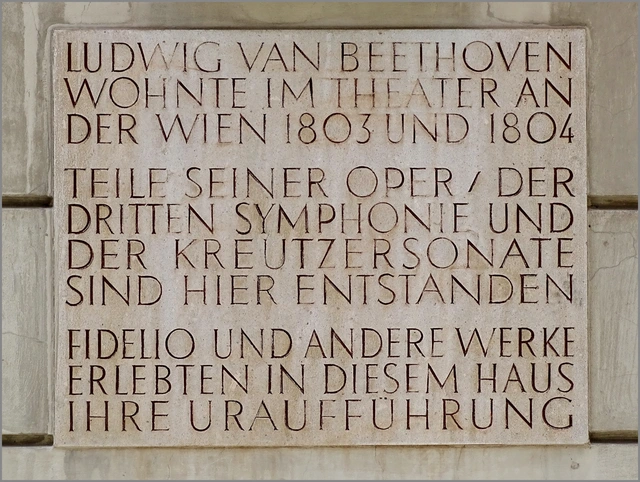

For a long time, performance venues such as the Theater an der Wien played something of a supporting role in official commemorations of Beethoven (Ackermann/Unseld, p. 17 et seq.). His residences, supposedly preserved just as he left them, had a far stronger appeal. As mentioned above, the first series of memorials to musicians established by the Vienna city authorities in the early part of the twentieth century was not continued until after the Nazis came to power. This was not a coincidence. Senior Nazi officials, including Gauleiter of Governor of Vienna Baldur von Schirach and Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels, turned composers into (Greater) German national heroes in audio form, and saw them as useful tools for consolidating the Nazi regime. Their efforts in this direction led to a distinctly nationalistic “popularisation” of certain composers, as exemplified by events like the “Reich Mozart Week” of 1941. Indeed, in a speech that remains infamous to this day, Schirach claimed that he who drew his sword for Germany was also drawing it on behalf of Mozart (cited in Trümpi 2017, p. 38).

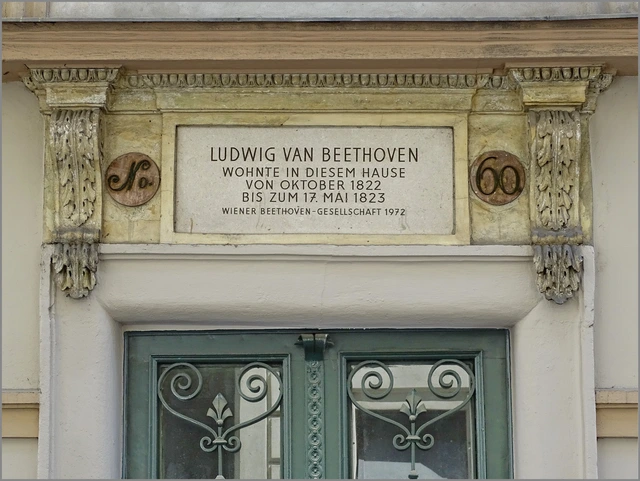

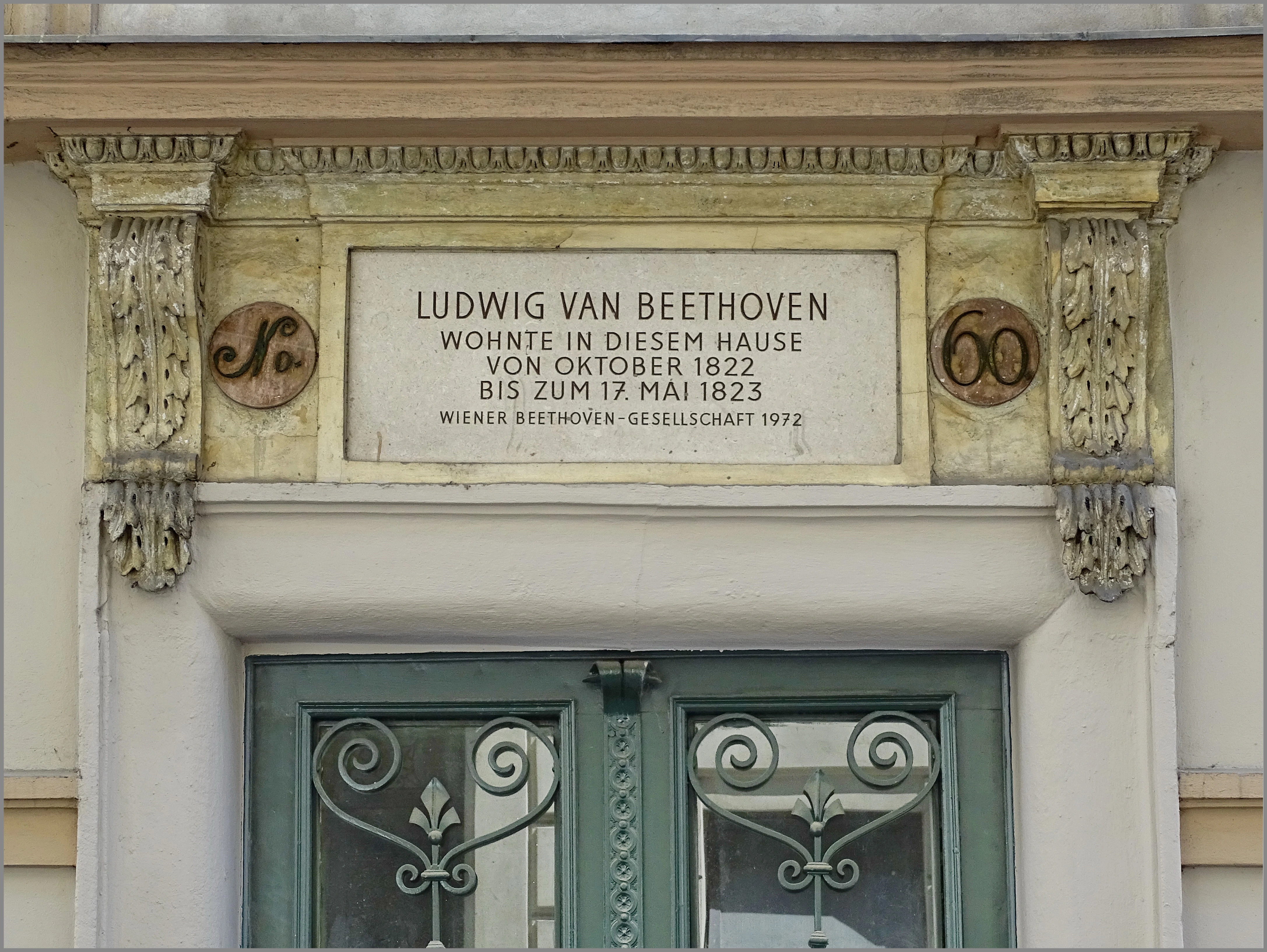

The apartments of these lionised composers could be styled and promoted as physical, walkable monuments to a German “national genius,” complete with a rarefied aura. To mark Reich Mozart Week, the Nazi cultural authorities opened three museums, dedicated to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, respectively. Haydn's “new” museum was in fact an update of the apartment in Mariahilf which, as mentioned above, had first been converted into a museum as far back as 1899. On the other hand, Mozart's museum was housed in an apartment at what is now Domgasse 5, while the first Beethoven memorial apartment was set up in the Pasqualati House, on the street now known as Mölkerbastei. The story of how the Beethoven museum was set up is particularly troubling. Despite the fact that the section of the Pasqualati House in which Beethoven lived at various times from 1804 onwards had actually been demolished in 1841 (something even the museum's director did not attempt to deny), the building was nevertheless chosen as the site of the first Beethoven museum. However, it so happened that the rooms chosen to accommodate the museum had previously been occupied by a Jewish family. The family had been removed from the property on the orders of the local Landeshauptmannschaft, or governor, with the Viennese press whipping up an anti-Semitic frenzy. On 11 January 1939, the Viennese edition of the Völkische Beobachter claimed they had been evicted “because these goons of an alien race were hogging the place where the greatest of musical geniuses lived, a place sacred to all Germans.” It went on to report that “The Jews fled from the building in all directions.”

I later discovered through my own research that the individuals targeted in this act of anti-Semitism were Josef Eckstein, an architect, and his wife Josefine, who was a dress-maker, along with her mother Rosa Hahndel and the couple's children, Hedwig and Clara. All five were forced out of their home on the Mölkerbastei by 20 June 1938. Josef and Josefine were deported to Theresienstadt on 24 June 1943, and on 23 October 1944 they were transferred to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. Rosa Hahndel died in Vienna on 9 November 1938, while Hedwig and Clara both managed to flee abroad. Hedwig left for the English city of Bristol on 26 November 1938, with Clara departing for the United States on 25 April 1940. In 1941, the Nazis turned the flat they had been forced to vacate into a museum dedicated to Beethoven. If we accept Heidemarie Uhl's claim that places of remembrance are there to “represent the national memory,” the story of the museum must be viewed as a particularly frightening case study.