In 1808, Beethoven received a tempting offer from Napoleon's brother Jéròme Bonaparte, whom Napoléon had appointed King of Westphalia. He wanted to appoint Beethoven as Kapellmeister at his court in Kassel, with an annual salary of 600 gold ducats. Beethoven was certainly inclined to accept what was a well-paid post, which would have meant leaving Vienna. His apparent willingness to take up the offer led some of his aristocratic patrons to make him a counter-offer in order to secure his services.

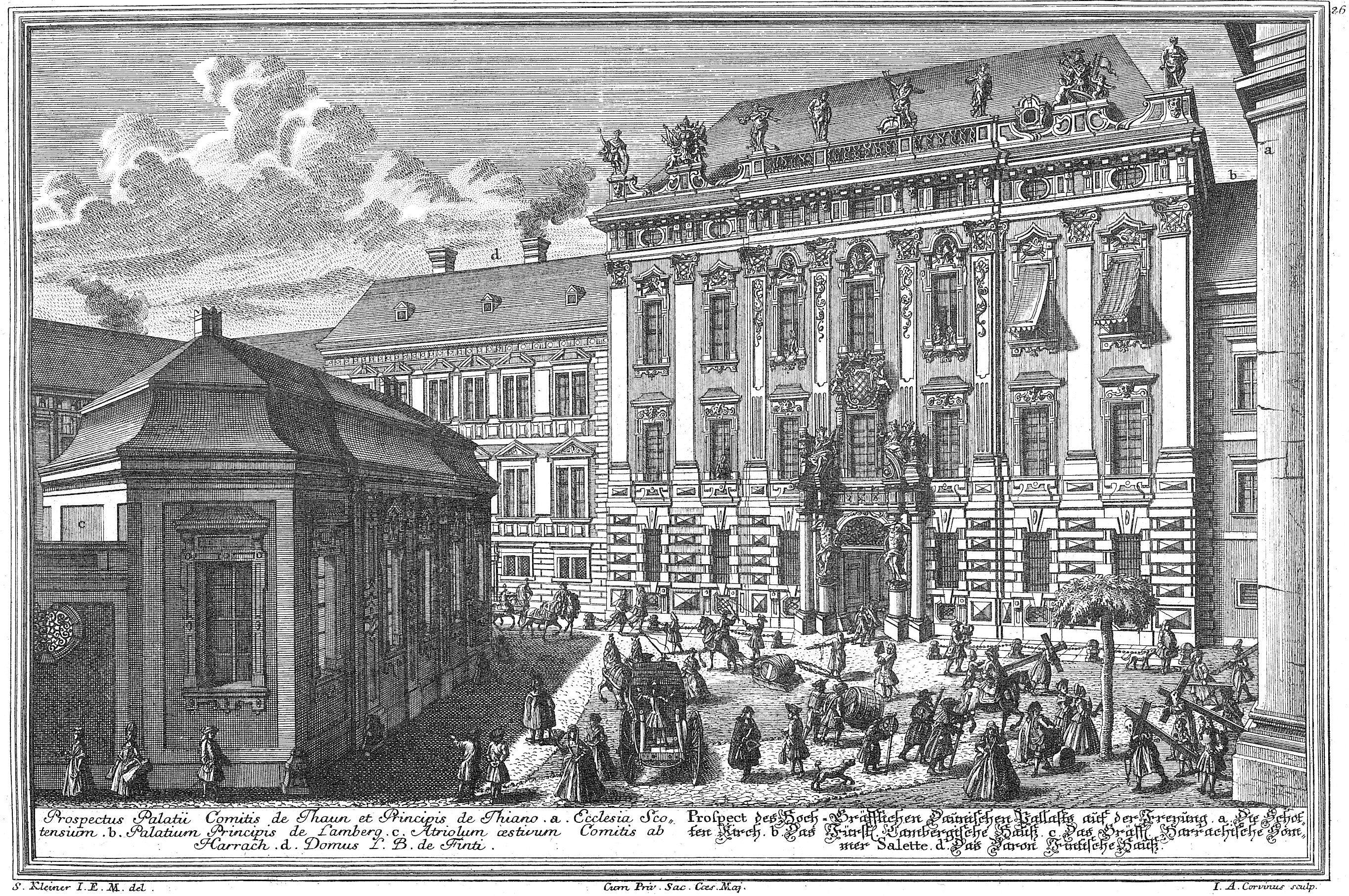

In 1809, Archduke Rudolph joined forces with Princes Kinsky and Lobkowitz to offer Beethoven an annuity contract worth a fixed annual sum of 4,000 guiders, with Kinsky and Rudolph putting up the lion’s share of the funds (1,800 and 1,500 guiders, respectively). Beethoven accepted their offer, which also obliged him to live in Vienna or the Habsburgs' hereditary territories, and not to leave these territories for any prolonged period of time.

The conclusion of the contract was followed by wrangling about the payments, and the disputes demonstrate the complex nature of the relationship between artist and patron. Beethoven received most of his regular payments from the Archduke Rudolph, to whom he dedicated a number of works following the conclusion of their agreement. He only received part of of the payment due to him from the Kinsky household in 1811, and the composer’s financial circumstances were further complicated by the death of Prince Kinsky in 1812, which forced Beethoven to press his claims against the prince’s descendants. Prince Lobkowitz went bankrupt in 1813, and Beethoven successfully asserted his rights under their contract in court.