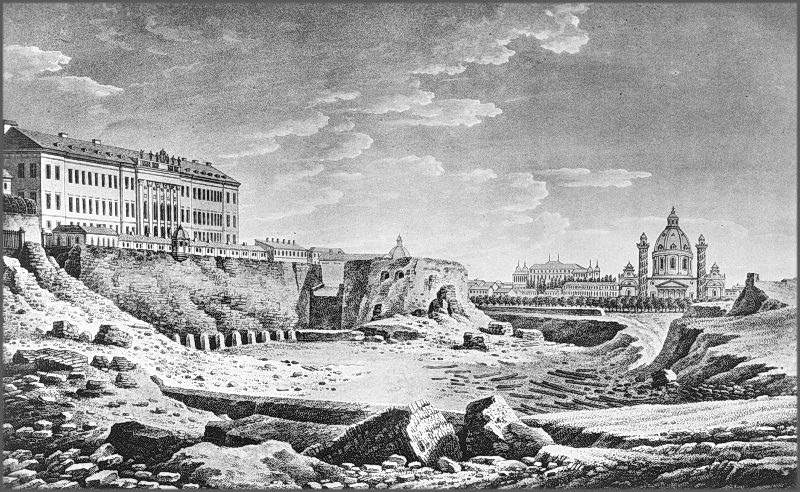

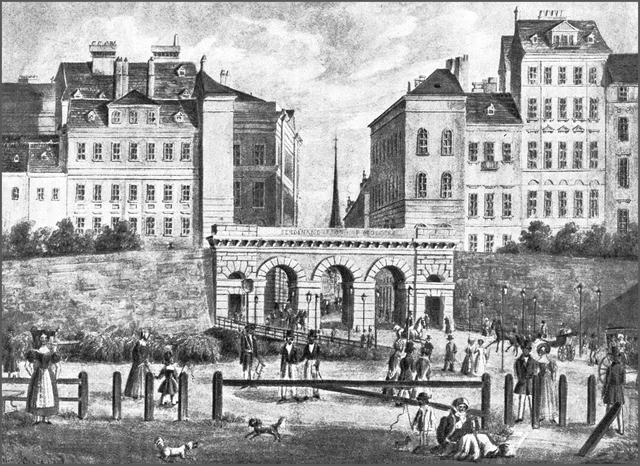

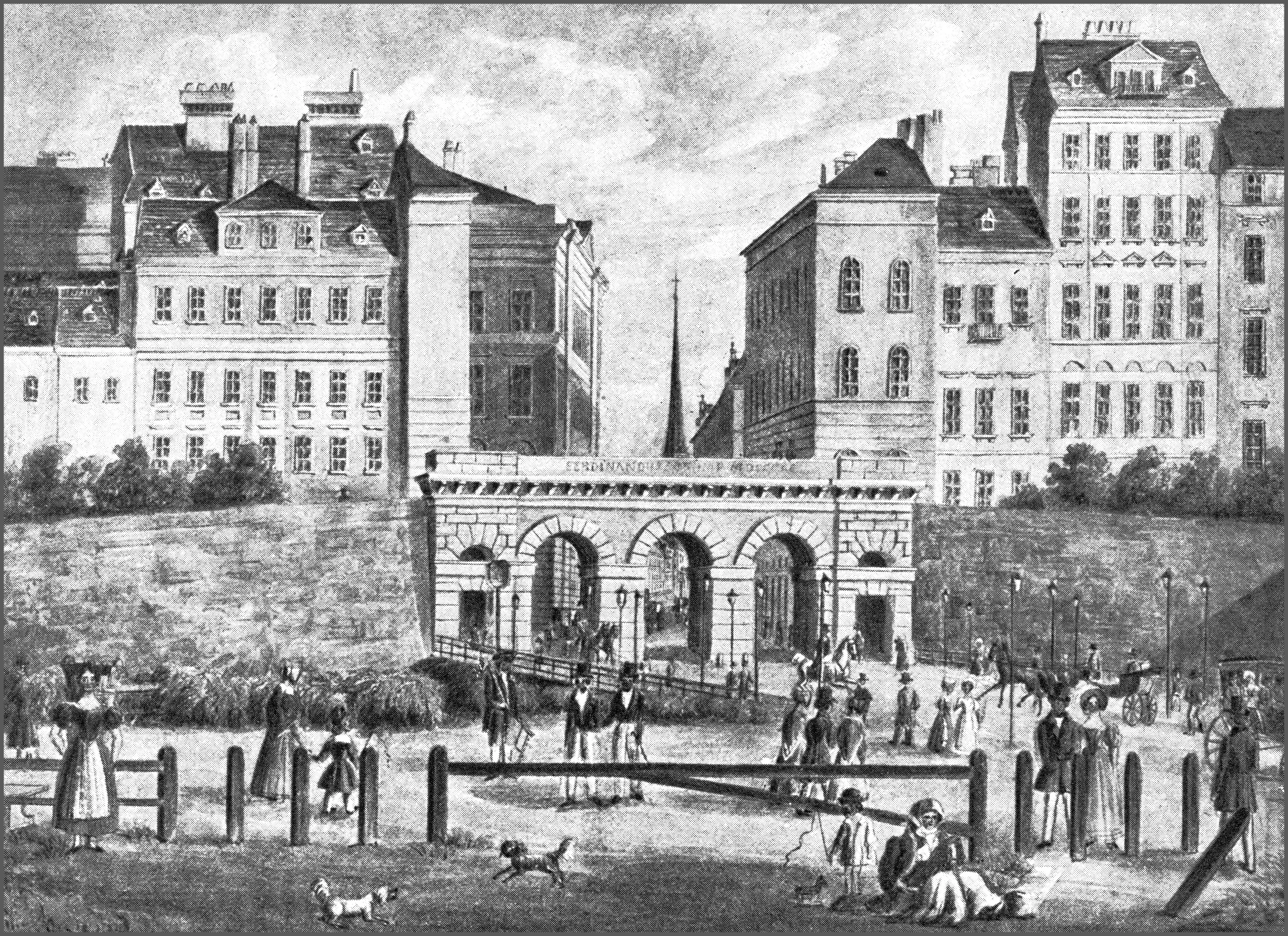

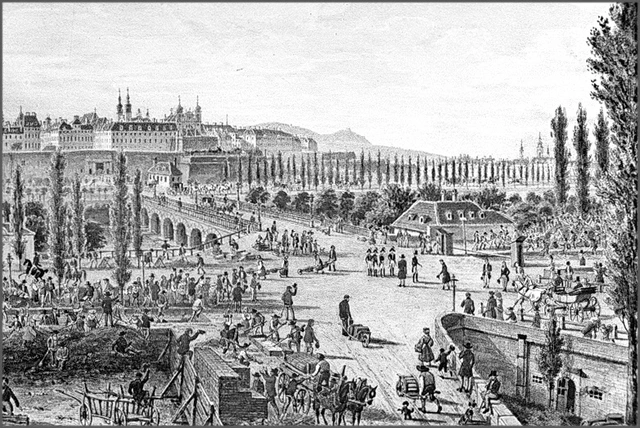

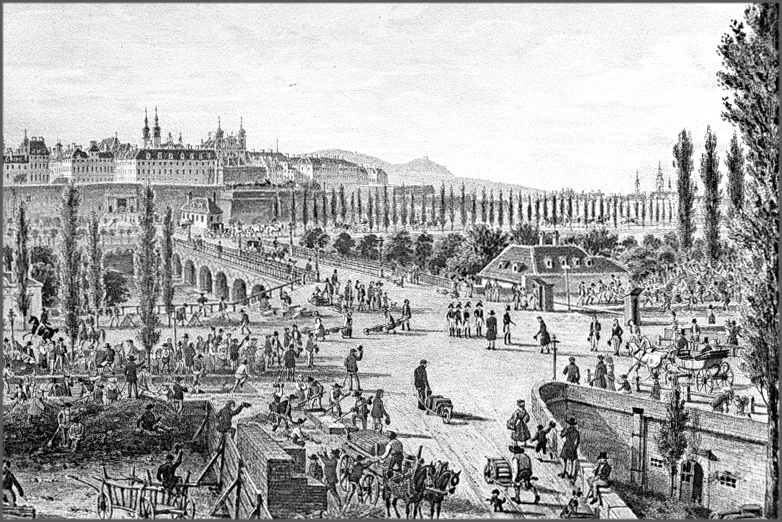

At the beginning of the 19th century, Vienna city centre was the seat of Habsburg power and the centre of its government. It was home to around 50,000 people and surrounded by its city wall. This defensive fortification, complete with bastions (forward gun emplacements), gates, a moat and a glacis (a clear, sloping area of ground originally intended to make the walls harder to access) was militarily insignificant by Beethoven's time, as the Napoleonic Wars demonstrated all too clearly; Vienna was occupied by the French in 1805 and again 1809. In 1805 the city was peacefully handed over to Napoleon's troops, and although a defence was attempted in 1809, the capital was eventually forced to surrender. The French blew up part of the city fortifications when they withdrew from Vienna, but it was not until 1857, when the structure was dismantled and made way for the Ringstrasse, that the fortified wall that had enclosed the heart of the city for centuries finally disappeared from the map.